Seizing Moments: Calvin Klein's Iconicity & JAW

Is capturing moments enough to be an iconic brand?

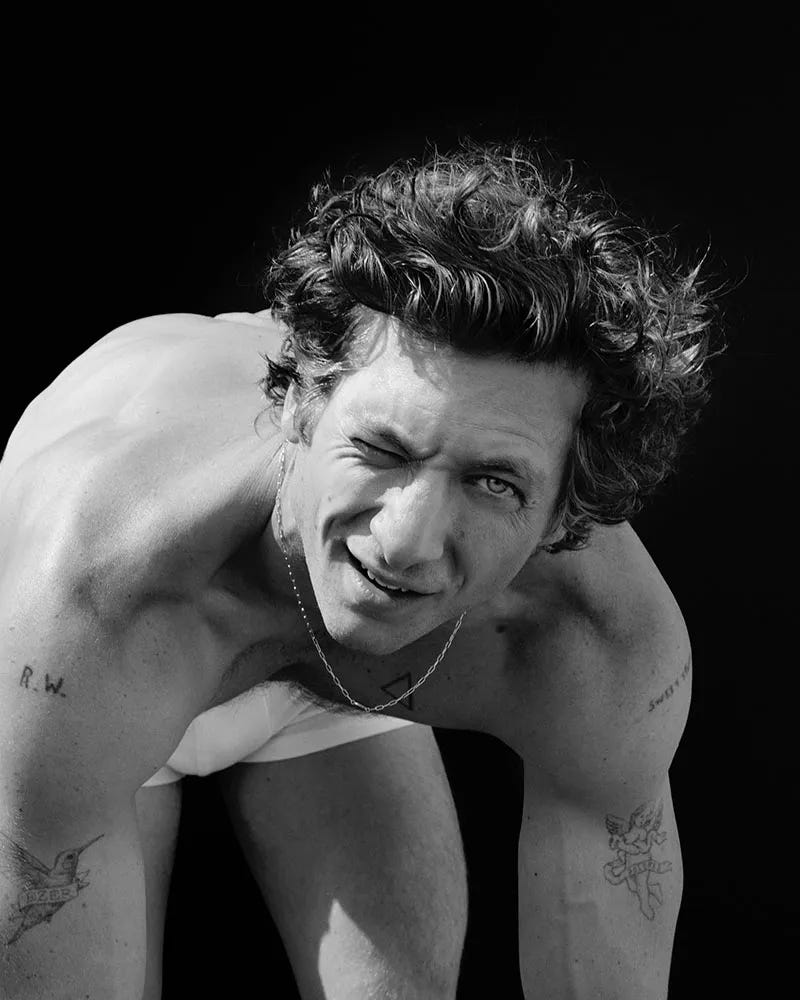

“HE IS THE MOMENT!”

That's an Instagram comment on the recent Calvin Klein commercial featuring Jeremy Allen White, summing up today's brandscape. It is all about seizing moments!

We live in a “moments” era. Every celebrity, brand, creator, show, and idea strives to “seize the moment" in a highly crowded marketplace, spending millions to capture fleeting attention across platforms. Seeking nods, winks, side eyes, or even frowns from audiences, tribes, or fandoms. Recently, Jeremy Allan White (JAW afterwards) had his moment in the spotlight with the popular Bear show on Hulu and a recent Golden Globe award. As JAW becomes the moment, it's no surprise brands want to ride that wave. Calvin Klein's recent ad had its own moment, capitalizing on JAW's current fame. Indeed, I was planning to write about another moment. But, when Calvin Klein (CK) moment took over, I had to give in. After all, it's all about moments— for everyone.

Social media and the blogosphere are buzzing with comments to the “eye-candy” commercial. Agency professionals discuss the spot's creative strategy, others reflect on the merit of those discussions, and some simply revel in the raw sensuality, admiring JAW's rugged and unpolished undress. Although I desire to belong to the last group admiring the perfect imperfections of JAW, my cultural strategist hat brought me in front of the screen to approach the spot more from an iconicity angle. Passionate curiosity is a curse and a gift… Mostly a gift. 😇

Let's briefly address tensions the commercial and comments raised. Will capturing the JAW moment sustain CK as an iconic brand? Will virality of the spot warrant its cultural impact?

1. IDEA or NOT?

Sir John Hegarty, the former creative founder of BBH Agency, recently critiqued Calvin Klein's latest commercial on LinkedIn. While acknowledging its strengths in aesthetics, casting, and music, Hegarty argued that the ad lacks a central idea. According to him, a successful ad should express a truth or insight, emphasizing the need for creatives to embrace the dictionary definition of an idea: "A thought or plan formed by mental effort."

Hegarty's critique gains significance, considering his prominent role in BBH's “accidental” global popularization of Y-front boxer shorts. This "accident" is explored later in this blog in Levi’s story and will shed more light on his emphasis on the “idea.”

The ongoing debate on social media questions whether an underwear commercial, or any commercial, requires a central idea or purpose. Some agencies challenged Hegarty's assessment, citing concerns about the male gaze and its credibility for this particular commercial. In contrast, a more third-wave feminist perspective from female audiences appreciates the aesthetics of Jeremy Allen White (JAW) and criticizes male media experts for their biased assessment.

Applauding the female gaze and any commercial supporting it — with or without a central idea expressed in the creative strategy and creative brief. But, the question remains: Should the ads - let alone an underwear ad - have an idea? Not necessarily. But, iconic brands do and should. The conviction and execution of this central idea through creative cultural codes are how these brands move the needle in the culture and also in business outcomes. Thats why Hegarty's critique becomes more insightful when reflecting on BBH's success with iconic Levi's campaigns in the UK in the late '90s. [Case Study: Levis at the end of the blog]

Indeed, CK commercials and campaigns always had an idea, embedding the contemporary gender ideals since the 90s. See the iconic Mark Wahlberg and Kate Moss 90s CK copy below. I think there is a gender idea in this JAW commercial as well, albeit not a well-executed one. Contrary to the notion of catering to the female gaze, the creative executes a non-gendered or queer audience gaze subtly veiled under the heterosexual man's body. Although the commercial doesn't explicitly address contemporary faultlines in masculinity and male sexuality like CK ads in 90s, it brings a sense of contemporaneity through Mert Alas's skillful camera work, integrating the queer gaze, without fully addressing the current gender ideologies and dynamics. [Note: There is a lot of discussion around the use of queer vs gay in addressing the LGBTQ+ audience. I welcome the opportunity to learn more if readers care to share their POV on the usage of "queer" vs. "gay" concepts about LGBTQ+ representation in advertising.]

Although the commercial doesn't explicitly address contemporary faultlines in masculinity and male sexuality like CK ads in 90s, it brings a sense of contemporaneity through Mert Alas's skillful camera work, integrating the queer gaze, without fully addressing the current gender ideologies and dynamics.

2. CELEBRITY OR NOT?

A tweet dissecting the commercial sheds light on a prevailing practice in agencies: compensating for weak creative briefs with celebrity endorsements. While somewhat harsh, the observation resonates. Riding on the coattails of celebrities poses a risk—campaigns may either lose the spotlight for their central ideas. Jordan-driven endorser formulas are outdated in the disintermediated brand landscape.

In mainstream brand management, the endorser strategy is about affecting the consumers’ attitudes toward products through celebrity endorsements. This intermediation strategy — putting the celebrity endorser in between the fan and the brand — has been effective when advertising was used to be the most prominent form of media communication. Yet, this strategy has become less effective with the increasing popularity of social media that fosters the disintermediation capabilities of brands; that is going directly to the consumer.

This particular Calvin Klein commercial has another celebrity problem. It features a myriad of celebrities and iconic brands: JAW, CK, Y-front white boxer, the New York skyline, and the renowned creative director Mert Alas. Not to forget the iconic soundtrack, "You Don’t Own Me" by Lesley Gore. The question arises: how many brands are too many for a 30-second spot to carry over to the iconicity line? Each one competes for attention without a central idea to anchor them. In this crowded stage, the absence of a unifying concept becomes evident, inviting criticism for lacking a central idea, truth, or purpose. The disparate brands in the spot float, imposing their own agendas and desperately trying to capture their individual moments without a cohesive narrative, lending credibility to the critique of a missing central idea.

3. ELEVATED AESTHETICS or NOT?

The film-like ambiance, the NYC skyline bathed in golden hour hues, and nostalgic nods to the '90s showcase impeccable aesthetic and creative choices in this commercial. Such excellence is expected from iconic creative director Mert Alas, who consistently brings a flawless creative vision to every campaign he leads—something I, as a big fan, appreciate.

However, CK's Y-front boxer, an iconic product, doesn't seem to receive the much deserved aesthetic elevation in this 30-second JAW spot. The white boxer, despite its iconic status, appears to get lost amid the proliferation of brands mentioned earlier.

In contrast, the contemporary marketplace employs diverse creative and aesthetic strategies, particularly in creating aesthetically elevated iconic products. Jacquemus, for instance, has mastered the art of aesthetic elevation for their iconic bags. Their playbook involves leveraging escapism as art direction, presenting products with relentless aesthetic excellence. Through an out-of the box content strategy featuring real and CGI images, Jacquemus transports viewers to a magical world reminiscent of Oz, effectively enhancing the appeal of their products. The similar creative and aesthetic elevation strategies can be identified for mainstream products like Le Creuset pans, Quip toothbrushes, Rothy’s flats etc

4. CULTURE MAKER or NOT?

When brands chase the wind of celebrity moments - relying on the fleeting allure of famous faces - then the brand strategy is reduced to capturing moments rather than creating meanings. This critique echoes my earlier posts on Peloton, Taylor Swift, and a growing epidemic of moment-centric brand management. The result? A modern fatigue in brands fixated on capturing moments, neglecting the essential work of genuine brand building. While moments can amplify brand meanings, they don't birth them. As Montell highlights in her book Cultish, "Meaning-making is a growth industry.”

Leading culture requires more than hitching a ride on a celebrity's moment. The strategy works when brand purpose aligns with the celebrity's values, as seen in Nike's Colin Kaepernick Dream Crazy campaign. Contrastingly, Pepsi's attempt with Kendall Jenner fell short due to a misalignment of purpose (in the very mildest form of critique for that cultural trainwreck campaign)

5. CULTURAL STRATEGY or NOT?

Aesthetics and sexuality have always been at the center of the CK creative strategies, particularly in '90s commercials like those featuring Kate Moss and Mark Wahlberg. These ads boldly tackled gender ideology about body, beauty, and sexuality. While the JAW commercial nods to this heritage, it misses an opportunity to confront contemporary gender dynamics, especially in masculinity. The filmic view and a Michaleangelo-esque body of JAW lack a central idea, limiting the ad's cultural impact to a fleeting eye-candy moment.

"When a brand weaves a valuable story, it earns authority to tell similar stories addressing identity desires in the future." CK possesses the cultural and political authority to delve into gender ideologies, having told such stories in the '90s. This campaign could have revitalized the brand's heritage and influence for the 2020s, but it opts for beauty over substance, epitomized by fashion photographer and creative director Mert Alas. The lack of a central idea hinders its cultural footprint, unlikely to influence sales.

Now, let's revisit the 'accident' Sir Hegarty mentioned—the Levis revitalization story, a masterclass in provoking gender codes by objectifying the male body and accidentally creating the Y-front white boxer icon.

CASE STUDY

Levi’s 501 Campaigns in UK by Bartle Bogle Hegarty (BHH)

Context: Levi’s Crisis in Europe

Levi’s, once an emblem of post-war youth counter-culture, faced a grim reality by the early 1980s—the brand lost its appeal among European youth, dwindling into a mere commodity. Facing a collapsing market share and contemplating a retreat from Europe, Levi’s hired the fledgling agency BBH in the UK, dispatching retail clothing veteran Rooney as a troubleshooter.

Solution: Subversive Revitalization

The solution emerged from appropriating provocative, gender-bending ideas prevalent in the British art scene, crafting a subversive, distinctly European reinterpretation of Levi’s American spirit of rebellion. Recognizing the need to engage with Levi’s heritage as a symbol of post-war rebellion, Hogarty’s creative team collaborated with Ray Petri, a renegade stylist immersed in London’s underground fashion movement. Injecting radicalism into Levi’s nostalgia, they blended provocative gender codes with homoerotic ads, challenging societal norms and objectifying the male body in diverse settings.

Results: The Levi’s Renaissance

The impact was swift and staggering. Levi’s sales skyrocketed, growing 600% in 1986 and another 1000% in 1987. The campaign single-handedly restored Levi’s to its former leadership position, symbolizing youth rebellion and becoming the must-have jean for decades. This avant-garde approach, pushing gender code provocations further, solidified Levi’s status as an enduring rebel brand—a testament to one of the most effective branding efforts in European business history.

[For more details on Levi’s campaign, refer to Holt’s Cultural Strategy Book]